Unexpected and dramatic precipitation events become everyday struggles as the effects of climate change can be felt more and more on our skin. Managing the response to this phenomenon requires multilevel and interdisciplinary effort from cities, regions, countries and transnational systems likewise. In this broad horizon, we investigated the coordination role of municipalities with regards to climate change adaptation and especially linked to water retention. The investigation was done by unfolding the case of Hungary, where the Ministry of Interior initiated projects piloting small-scale nature-based water retention measures and examining the role of municipalities in the topic. We explored the above issue with Dr. Miklós Dukai, State Secretary for Municipalities of the Ministry of Interior, Ms Zsuzsanna Hercig and Dr. Petra Szatzker, project managers of two major projects in the topic: LIFE-MICACC (Municipalities as integrators and coordinators in adaptation to climate change) and LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS (Integrated application of innovative water management methods at river basin by coordination of local governments).

In the EU funding programmes of the 2021-2027 period, in line with the European Green Deal, priority will be given to developments that contribute to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and adaptation to the negative impacts of global climate change. One of the key elements of the objectives and measures listed in the EU Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (COM/2021/82) is the promotion of nature-based solutions. The role of local authorities in climate adaptation is crucial, as they represent the territorial level that can effectively communicate with local actors and integrate different interests.

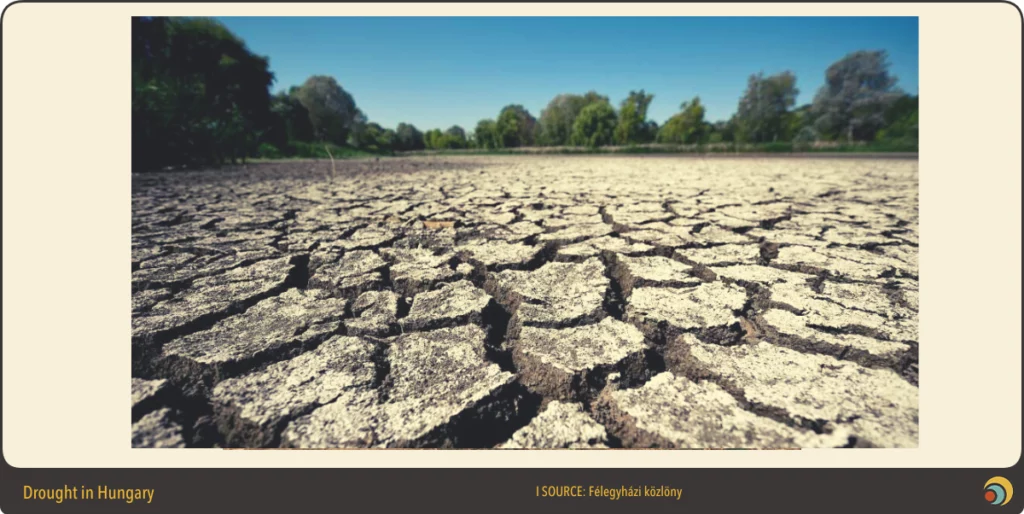

The issue of (nature-based) water retention is of particular importance in Hungary, both at national and local level. Due to climate characteristics (moderate climate with a significant continental influence) the primary foreseen impact of climate change in Hungary is the uneven distribution of precipitation, floods and droughts. Because of its location (plain surrounded by mountains) the country’s territory is more vulnerable to climate change’s negative effects than the European average according to the Climate Change Knowledge Portal, and agriculture is the sector which is most vulnerable to climate change. In line with the global and European trends, Hungary has also observed major changes in its regional climatic conditions in the last 100 years and more intensely in the past 30 years. According to the systematically collected and evaluated climate data series of the Hungarian Meteorological Service, climate extremes such as heatwaves, droughts and flash floods, floods have become more frequent in Hungary due to global warming. An increasing length of drought periods during all seasons can be observed in the trends.

In order to exploit the potential of natural water retention measures (NWRMs), the State Secretariat for Municipalities of the Ministry of Interior supports the preparation of local authorities for climate adaptation, collects and presents good practices in the country through EU funded projects, and seeks to create the right legal and policy environment for their dissemination. A milestone in this work was the LIFE-MICACC project under the LIFE Programme’s Climate Action sub-programme, coordinated by the Ministry of Interior, which demonstrated the potential of nature-based water retention at the municipal level in the case of five pilot municipalities, representing five different natural and geographical contexts.

The experience and results of this “ahead of its time” project were taken forward to the LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project from 2021 onwards, which aims to develop integrated water management solutions at regional level. The next step will be the NBS4LOCAL Interreg Europe project, to be launched in March 2023, where partners will work together internationally to find solutions to improve the policy environment. Dr. Miklós Dukai, State Secretary for Municipalities and the project managers of the two related LIFE projects were asked about the foreseen and already experienced impacts of the projects, the possible policy implications and the role of the Ministry of Interior.

BURST: Following the historic drought that spiked during the summer heatwaves of 2022, the importance of nature-based water retention measures became clear. However the LIFE-MICACC project has been brought to life as early as 2016. What prompted this very forward-looking project at that time and what was the Ministry of Interior’s main objective in launching it?

Dr. Miklós Dukai: In 2016, we approached all municipalities in Hungary with a questionnaire designed to explore the resilience of municipalities to climate change. We prepared the survey in collaboration with colleagues from the water sector and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). The fact that a significant proportion of local authorities gave very relevant responses confirmed the relevance of the topic and this led to an intense dialogue. The 899 completed questionnaires showed quite accurately the challenges faced by local authorities in this area: the five types of areas or problems that are specific to our country and that were represented by the five municipalities involved in the MICACC were clearly identified in the area of water retention and drought.

Ms Zsuzsanna Hercig: Already in 2015, the idea of a project to address the negative impacts of increasingly extreme weather events due to climate change at municipal level was raised, and to provide practical alternatives to compensate for periods of water stress or even water scarcity, using nature-based solutions. The idea finally turned into reality thanks to the European Union’s LIFE Programme, which supports environmental, nature conservation and climate policy objectives. We submitted our proposal in autumn 2016, which was preceded by the aforementioned online survey in February 2016 to identify the municipal partners that would serve as pilot sites.

The responses were filtered according to professional criteria, we also consulted with a number of municipalities by email and telephone, and even visited potential intervention sites during field visits. In the end, around 30 municipalities remained on the list, all of which showed some of the typical problems mentioned above. Out of these, the most relevant five were directly involved in the LIFE-MICACC project, the others were involved as collaborating partners, participating in the trainings and study trips to abroad, and with our help five of them made a replication plan too.

BURST: The LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project aims to plan and implement natural water retention measures at regional, river-basin level. What has led to the development of this second project and what are the new challenges faced when developing solutions on a river-basin level compared to local level interventions?

Dr. Miklós Dukai: While in the LIFE-MICACC project we developed solutions with individual municipalities, in the LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project we are focusing on catchments with different characteristics located around the two partner municipalities (Püspökszilágy and Bátya). And this is where one of the most important aspects of the whole water retention issue comes in, at least from a municipal perspective for sure: cooperation at the level of the catchment area. In the area of Püspökszilágy, for example, the municipalities along the Szilágyi stream, which are similarly affected by flash floods, and other stakeholders were involved. Water, on the one hand, does not look where it flows, and on the other hand, the functioning of water bodies is itself a very complex issue. So the management of water courses might be seen differently by a water officer, a forest ranger, a farmer, a landscape architect and a civil engineer. The local municipality is best placed to play a coordinating role, bringing together those with different interests and with the appropriate knowledge. Doing all this without neglecting the diverse attitudes can bring together interests around the common value of water retention.

Dr. Petra Szatzker: The role of municipalities in natural water retention is a relatively new issue, even at EU level. Even in LIFE-MICACC has already local government project partners but LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS aims to give the municipalities the know-how for the reconciliation of diverse interests. So-called Multi-stakeholder Catchment Forum has been established in both demonstration areas which provide a common platform for synthetizing the wide-scale professional, legal, technical and environmental aspects with the coordination of the partner municipality. In the whole process of planning, constructing, permitting and implementing green and blue infrastructure is a really complex and challenging task in which several different field of expertise are affected. It is essential that all of them are involved from the beginning to all of the professional aspects will be integrated into the process. Moreover participating and involving of all stakeholders makes the results of the project more successful and widely adopted by local people and experts. In this way the sustainability of them is also provided. The experiences and knowledge of the Forums will be shared with stakeholders involved in other river basins.

Dr. Miklós Dukai: Finding and developing common ground on the local, neighbourhood scale of nature-based water retention is the biggest challenge and the greatest achievement. The main achievement of LIFE projects is clearly in the field of awareness raising. We have taken many small steps that go beyond ourselves. We have managed to break through interests and even decades-old entrenchments. I would even say that we have broken through a certain glass ceiling: nature-based water retention has clearly become a factor in territorial development policy and funding instruments, and its potential and added value are taken into account at all levels of planning, from the ministry to local governments.

When we started in 2016, people didn’t really understand why we were doing this. Local authorities as well as some professional organisations didn’t understand. But time has proved us right, even before the extreme drought that peaked in 2022, it was clear that the surplus of the winter precipitation must be maintained by any means, because climate patterns show that we will have less than usual precipitation during other parts of the year.

It is therefore a great achievement that today nature-based water retention is included in operational programmes, it has been incorporated as a kind of horizontal principle in development policy and in regional development. It is an important result that in the case of urban stormwater drainage, for example, or in road construction, the need for water retention is already being considered by decision-makers. So there is now a new approach to this and many people want to address it. It is not a simple issue, however, because many interests have to be reconciled.

BURST: The LIFE projects work with local actors on local solutions, but the new project (NbS4LOCAL) that is now being launched under the Interreg Europe Programme aims to develop proposals for more effective policy support for the use of nature-based solutions by international partners working together. What could be the main directions of this process?

Dr. Miklós Dukai: I think the most important thing is that the change of approach that has already begun is effectively followed by legislative fine-tuning, with appropriate standards and manuals for new types of solutions. In addition, there are obviously many other good practices that have not yet entered the national thinking and legislation, and we look forward to seeing some of them in the new project.

Dr. Petra Szatzker: It is important to underline that in addition to the Multi-Stakeholder Catchment Forums established under the LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project, we have also initiated stakeholder consultation at the national level to make a supportive legal environment. The Integrated Support Board has 23 members, including the disaster management directorate, the regional government offices, permitting authorities, specialised authorities, all the disciplines without which no legislative change can be made, and which are needed to ensure the long-term sustainability of the project results. The members are not only involved in the project at the information level, but also participate in field visits, the operative work of the Multi-Stakeholder Catchment Forums and collaborate in the production of technical materials. The “glass ceiling effect” mentioned above has led to an increase in the number of professional organisations interested in collaboration, and we already had to expand the membership of the Board.

Ms Zsuzsanna Hercig: The LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project also involves organisations as partners such as the Hungarian Chamber of Engineers, the Faculty of Water Sciences of the National University of Public Service and the General Directorate of Water Management. In this way, the project will also help to raise awareness of currently practising and future water professionals. On the one hand, the methods developed, the experience and knowledge accumulated will be incorporated into the curriculum, and on the other hand, guidelines and templates will be created for engineers. This is very important because we have already found in the LIFE-MICACC project that some solutions for nature-based water retention are so novel that there is not necessarily a coherent body of experience and regulation, or even terminology, for their design. This is not only important for professionals, but also for local authorities, as it helps them to understand how to get started, what to expect and where to turn for help when designing a natural water retention measure.

Dr. Petra Szatzker: In fact, the knowledge building materials to be prepared with the help of the 23 professional organisations participating in Integrated Support Board will be integrated in the mandatory training courses to the given area of expertise.

BURST: To what extent are the results of the LIFE-MICACC projects known in other municipalities, or is it possible to know whether these solutions have been adopted elsewhere?

Ms Zsuzsanna Hercig: It is difficult to measure and quantify. What we do know for sure is that at the end of the LIFE-MICACC project, five so-called replication plans (municipality-level plans modelled on the five pilot developments) were prepared, and the municipalities concerned are seeking to implement them and are looking for funding opportunities. At the end of the project, partnerships at river basin level (around the five pilot sites) were also established, in which the municipalities concerned outlined common visions. To some extent, cooperation and joint thinking has started in all five river basins. In terms of implementation, two catchment partnerships (Bátya and Püspökszilágy) have been included in the LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project.

Interest from municipalities has been continuous throughout the LIFE-MICACC project. At several events municipal leaders turn to us with their ideas and suggestions, which sent us the message that the topic is important and is worth addressing. In fact, we have received information that the solutions we have developed are active study visit spots for mayors considering similar developments in their own municipalities. The project also produced an adaptation guide to help municipal leaders get started. And a granting program for small-scale initiatives of municipalities has recently been concluded in the framework of the LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS project.

Dr. Miklós Dukai: This granting program supports 15 municipalities’ projects to implement small-scale nature-based (green-blue) solutions, including natural water retention measures and climate change adaptation, out of the approximately 90 applications received. It was important to have national coverage, to have a broad spectrum of innovative solutions and to support also smaller municipalities. The initiatives are small-scale but complex in their approach. In Gyenesdiás, for example, water retention is encouraged by the distribution of water collection vessels, but there is a strict requirement that residents need to use them to water vegetable gardens. In the 17th district of Budapest, a concrete area covered with asphalt between panel buildings will be broken up to make room for the green, and nature-based water retention system will also be created. I think this also shows that water retention has entered the public thinking. Now we can take the next step: hopefully, landscape-scale water retention will be also included in EU funding in the coming years, as it is expected from the EU.

BURST: One of the importance of the two LIFE projects is that they involve small-scale but complex local initiatives. What is the obstacle for supporting such small-scale local initiatives in large numbers through national operational programmes?

Dr. Miklós Dukai: At the moment, the energy crisis has dragged everything through, it is difficult to talk about planning for the future and the situation has made energy efficiency projects much more of a target. Despite the fact that, at least at the settlement level, there is currently less focus, the original mission of the Ministry of Interior on nature-based water retention is still alive. In this situation, there is a higher social interest in running a day care centre in a settlement, for example. But if development takes place, we hope that as a result of the sensitisation of local leaders, the issue of water conservation will be addressed in as many places as possible. We are also confident that we can continue to seek direct EU funding in the future and further broaden the horizon of local authorities in this area.

Dr. Petra Szatzker: It is important to add that the results of the LIFE-MICACC project also strongly contributed to the inclusion of water retention as an additional element in the TOP Plus and KEHOP Plus national level EU funding programmes. As a result of the awareness-raising achieved with LIFE projects, the use of these funds can also become much more effective in terms of water retention, which can be integrated into and complement other development activities. This will also support the use of nature-based solutions and their widespread adoption.

BURST: In 2022, climate change will be upon us from the doorstep, which will certainly accelerate the breakthrough of the ominous glass ceiling on water retention. Are there any plans for the Ministry of Interior to focus on other areas of climate adaptation and nature-based solutions?

Dr. Petra Szatzker: In the LIFE projects we are indeed focusing on the role of water in adaptation, and on the issue of water retention. However, in the LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS granting program for small-scale projects, we deliberately opened up the topic, not only focusing on water retention, but any nature-based (green-blue) solution related to climate adaptation could be applied for. The program clearly revealed that local leaders are interested in also climate adaptation not only water retention and thinking in integrated solutions.

Dr. Miklós Dukai: Blue and green infrastructure development are completely intertwined, and any solution for nature-based water retention is complex and deeply rooted in the local context. The Sóstó development in the outskirts of Székesfehérvár is a good example of the complexity of the issue: treated wastewater contributes to the complex rehabilitation of a wetland of conservation importance, the landscape has been restored, and recreation, environmental education and health were also important considerations. All this is the result of the coordination of the local government. We have really focused on water retention, mainly because of its complexity. Our vision is that every second or third municipality will implement natural water retention measures in the future with this complex approach, and that this approach will be integrated into everyday life and households. At the same time, there is no doubt that another milestone in this change of approach will be the forthcoming introduction of support for nature-based solutions in agriculture, where farmers will be producing ‘nature, environment’, for example by allowing their former arable land in the low floodplain to be flooded in return for compensation for the ecosystem service thus provided.

We had the privilege to explore the above topic with Mr. Miklós Dukai, State Secretary for Municipalities of the Ministry of Interior, who has been advocating for the topic by initiating such projects since 2015. He has been working in central governance bodies since 2010, and was appointed State Secretary in May 2022. He explained to us the Ministry’s undertakings and lessons learnt in two major projects: LIFE-MICACC and LIFE LOGOS 4 WATERS, together with his colleagues leading the projects.

The interview was prepared by Ms. Mónika Németh and Mr. Ferenc Albert Szigeti, experts of BURST and coordinators of TeAM HUb, the Hungarian NetworkNature Hub for Nature-based Solutions in Budapest 23rd January 2023.