As weather is getting more and more extreme, more and more areas in the world (including much of Europe) experience more and more drought events. However, much of the water we have at our disposal is wasted – both greywater (i.e., non-contaminated household waste water) and rainwater, currently usually disposed of. The question is, could it be used for domestic and municipal purposes, and how can this be achieved? We talked to Anacleto Rizzo, partner of Iridra, an Italian company researching this issue, to learn more.

As a starter, could you please introduce Iridra, and maybe yourself as well?

Anacleto: To start with myself, I’m a hydraulic engineer and I have been a partner of Irida for six years. At Iridra, we plan and design nature based solutions for sustainable water management, and then supervise their construction. “Nature based solutions” (NBS) is a fairly new concept with a wide range of applications, and we deal with NBS in relation to water treatment – i.e., constructed wetlands and rainwater management NBSs (sustainable drainage systems, water sensitive building design, low impact development). These solutions are fostering circular economy and climate change adaptation as well.

Could you explain the importance of water management in climate change adaptation – or even prevention?

Due to climate change, we can expect a change in rainfall patterns, which is leading to an increase in droughts and very heavy rainfall, an increase which will accelerate in the future. So, we have a challenge to adapt cities and urban areas to changing rainfall patterns. To put it very simply, we have to deal with a lot of water within short periods and with lack of water for longer and longer periods. This is how water management is crucial to climate change adaptation.

So: how can NBS help us adapt to droughts?

NBS can play a role in providing non-conventional water, i.e., by turning wastewater into water that we can use again. This water can never become potable (we will not be able to drink it), but wastewater can be treated and then be used, e.g., for toilet flushing and for irrigation (watering plants), thus reducing our water needs and helping us grow plants in drought seasons. Finally, if we use this treated wastewater for irrigation, that can support us in greening our cities, which will reduce heat islands.

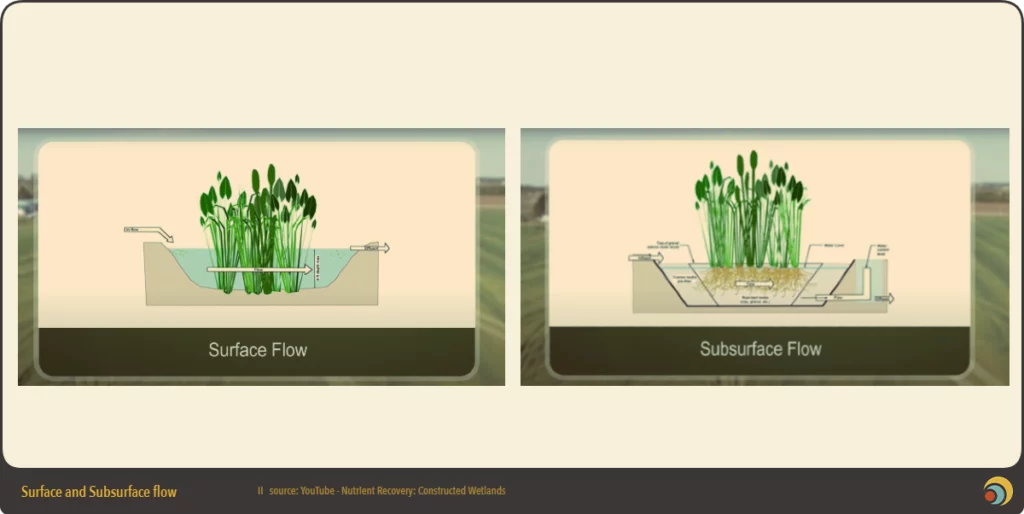

Of course, we cannot use any kind of wastewater for this purpose. There are two sources of non-conventional water: rainwater and household wastewater not contaminated by faeces and urine, so wastewater from showers, kitchen sinks and the like. This is called greywater that can be treated by NBS. An example for NBS to be used is the so-called “constructed wetland”, but we are exploring the possibilities of using green roofs and green walls.

With regard to both rainwater and greywater, why should you treat them instead of just collecting them and directly reusing them?

For rainwater, you could use a simple mechanical filter to remove particulates, but an NBS, such as a rain garden, costs almost the same and is much more effective in blocking pollutants from roofs and pavements. Greywater could also be treated by technological solutions. Actually, technological solutions take up less space, around the size of a washing machine, while NBSs are more space demanding, but they consume less energy. And there’s a major added value of NBS (in general, not just for water): it has additional benefits beyond its main “job”, such as increasing biodiversity or greening cities. NBS provides different benefits in one shot, which is a main advantage compared to other solutions.

Moving on to Iridra, could you give examples of projects you have worked on?

Iridra has two main focus areas: one is to design NBS based systems, but the more interesting one is that we are involved in R&D, where we are testing innovative NBSs. For example, we participate in a couple of Horizon 2020 projects, like HYDROUSA, where we try to reduce wastewater in food production, trying to apply NBS to wastewater. Another interesting project is NAWAMED, where we test green walls for greywater treatment, to be used in Mediterranean areas with high risks of water scarcity. For example, these solutions will be installed in Southern Italy, Tunisia, Lebanon and Jordan. In the NICE project, we test green walls for water treatment in Turin, Italy. We then try to put these solutions into real use.

Are you also active on the market, can I contract you to plant NBSs for greywater in my house?

It’s easier to answer that question if we use technology readiness levels (TRLs), as they do in Horizon projects, to shed light on the market readiness of these solutions. Some solutions have low TRL, so they cannot be marketed yet. Green walls, for example, are quite innovative as a water treatment NBS, they have been tested for this for only a couple of years. However, some NBS are much readier to be marketed, have higher TRLs, like constructed wetlands, where we have 20 years of experience. So some tools in our portfolio are more ready to the market than others, but in general, we don’t sell anything. What we do instead is a tailor-made approach in projects on how to use NBS. Because solutions need to be tailor-made, it doesn’t make sense to talk of simply selling products on the market anyway.

If a municipality is interested in NBS for water treatment, how should they start their work?

It really depends on the funding, on the willingness to make investments and to maintain them. We see and expect climate change adaptation investments. We suggest that municipalities have very good European project offices that are looking for investment funds where they can apply to calls for proposals. This involves R&I funds but also investment and development funds. There are increasingly many climate change adaptation-related funds that can be used for exactly these kinds of issues: greening cities, biodiversity, adaptation.

In Italy, what we also see with regard to the Green Deal, is that municipalities cannot obtain funding because they are not ready with design for the project. So what I would advise is that while it’s not enough to have an idea, municipalities need to have action plans and basic designs ready, so when funds open, they are ready to apply for funding with feasibility studies and basic designs estimating budgets and outlining what needs to be done.

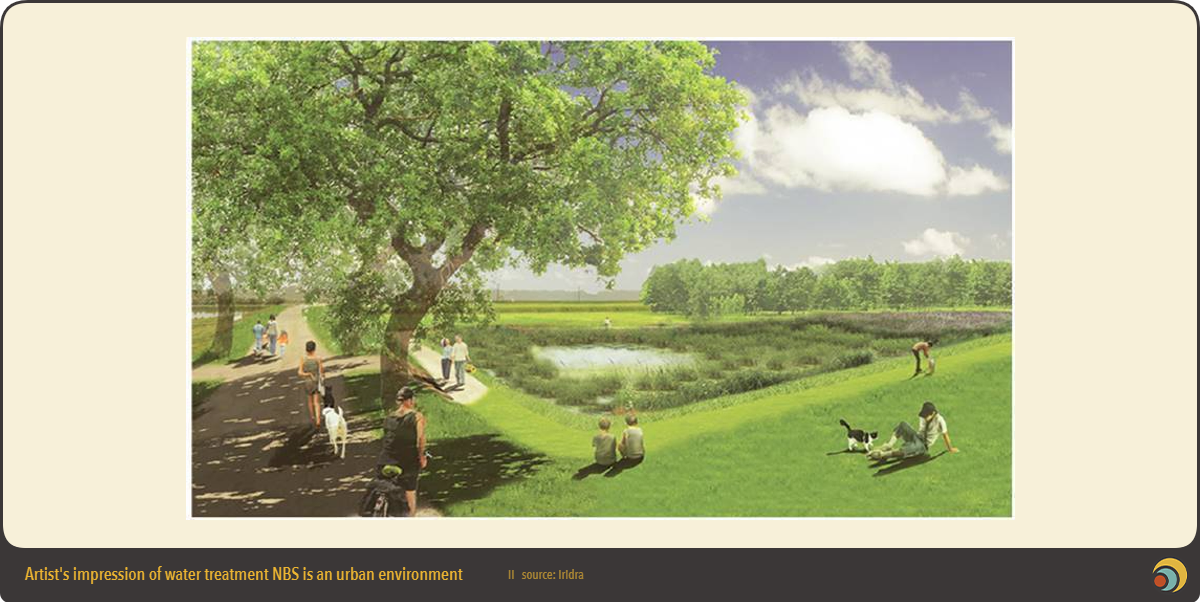

How do you think municipalities can sell such NBSs to themselves and to the public? As I understand, constructed wetlands take up quite a lot of space – so how to convince a municipality to use a free area as a constructed wetland, as opposed to a park, or for housing?

In such cases, there are two options. First, you can use buildings as skeletons for NBS instead of building NBS on the ground, i.e., you can use green walls or green roofs. On the ground, the only space you can use are parks. Parks are public spaces and you cannot force people to like parks being used for NBS. However, to avoid conflicts as much as possible, a bottom-up approach is always preferable. Citizen involvement and co-designing can popularise NBS. So, if you want to adopt NBS in cities with sparse space, it is better to start by engaging the local public, that will generate support for these innovations. Otherwise, even if you have the nicest park ever, you will still end up with public dissent around NBS as they are not on board with it. That’s why bottom-up approaches and shifting the mindset of the public is so crucial.

If the municipal leaders reading this want to look ahead, there is a really crucial question to ask here: what is the next big thing in water treatment NBS? Beyond green walls, are there new technologies being developed and ready to be used in 5-10 years?

NBS is not about innovation as we normally understand it. Even when we talk about “innovative” approaches, that is mostly about figuring out using existing “technologies” (so to speak) for new purposes. For example, we need to optimise how green walls can be used for greywater treatment, but NBS experts already know how to design green walls in general. Green walls, green roofs, sustainable drainage systems and so on are known technologies that are being used all over Europe (the Water Square of Rotterdam is an excellent example for how).

Considering the next 5-10 years, instead of looking forward to the “next big thing”, we should focus on increasing the number of experts in water-treatment NBS.This is because when you plan future urban developments, NBSs need to be planned in advance. If you do not plan NBSs at the beginning, you will not be able to change your plans to accommodate them. And to accommodate them early on, you of course need to have the experts available.

A key slogan I would suggest to municipalities is “water-sensitive urban design”, which tells urban designers that they need to be sensitive to water. They need to remember that water exists, for example, when designing new building blocs. Currently, designers start with the buildings and the roads and the parks, and then involve hydrological engineers to design a couple of pipes. However, there is no space for water treatment NBSs anymore. You need to shift the mindset: prior to anything else, they should look at how water is running in the area, and try to be respectful of water-related issues. This means designing the NBS before anything else – otherwise, cities will not be ready for challenges ahead.

Anacleto Rizzo is an expert in water sustainable management (saving, reuse, recycling); nature-based solutions for wastewater treatment (constructed wetland); water management and climate change adaptation policy; ecosystem services; green infrastructure; sustainable drainage systems (SuDS), cosdesign of Nature-based Solutions with citizens and stakeholders. From January 2015 in-house consultant in Research, Development, Dissemination and Design for Iridra Srl; from April 2018 he became partner of Iridra Srl. He worked on more than 50 among feasibility studies and design projects on his specific topics (e.g., constructed wetland wastewater treatment plant or SuDS components). He worked since 2018 and is currently involved in 5 R&D EC Funded projects (H2020: HYDROUSA, PAVITR; MULTISOURCE, NICE; ENI CBC MED: NAWAMED). He is author of 25 papers published on international peer review top-ranked journals and 12 book chapters as well as Editor of “Wetland Technology: Practical Information on Design and Application of Treatment Wetlands” (2019, IWA Publishing) and “Nature-Based Solutions for Wastewater Treatment” (2021, IWA Publishing). He is also within the Editorial Board of Science of the Total Environment and collaborates as reviewer for different top-ranked peer review journals (e.g. Ecological Engineering, Water Science and Technology).