Interview with Christophe Gouache

Christophe Gouache is a designer, researcher and combattant for co-creation and participative design, and our interviewee this month. Among various projects he acts as Lead Expert of Active Citizens URBACT Action Planning Network, concentrating on the topic of forms of citizen participation in governance – this is why we contacted him to guide us through this topic. Being a great storyteller and passionate visionary of participatory scenarios, we definitely recommend you to stop him for a chat if you bump into him eating waffles in Brussels or anywhere else in Europe.

“The aim of Active Citizens is to rethink the place of the citizen in the local governance by finding a balance between representative democracy and participatory democracy, focusing on small and medium sized cities.” What are your experiences and takeaway lessons in this project so far?”

The 8 cities participating in the project have different levels of advancements regarding the question of participatory democracy – thus they have mixed profiles, which means that we need to work on very different aspects. One of the natural challenges is that citizen participation is not in the DNA of national authorities: they don’t know how to do it, they have never been asked to do it; and suddenly they are asked to work with citizens both on urban planning and on policy making, of course they have no idea how to do it. On the political side we need a huge change of posture and attitude: elected representatives need a behavioural change, an evolution of their own role, where they should be the guarantee of the process of participation of different people in decision making rather than doing it on their own. One would say we have a generational gap here, but I would rather say their attitude mostly depends on how long they have been in politics. Either you have a fresh view on how to do politics or not, doesn’t matter whether you’re old or young. The last actors of the citizen participation game are the citizens themselves: depending on the country there is a huge work to do on rebuilding connections and trust with citizens; who also need to be trained to be able to collaborate with the city administration.

If you really want to work on heavy policy-making or co-creation of strategies, it’s not about asking citizens to decide the colour of the benches – it is to co-design the future climate plan. For that you need to change the way of working with them. Even in best-case scenario, the cities are very much in a complaint-oriented mindset when it comes to dealing with people’s problems: I allow my citizens to complain and on city level I will try to find a solution – this also needs to change. We say that citizens have the expertise and legitimacy to participate in finding solutions as well.

What do you think are the factors which enable the cities to really understand the need and proceed towards citizen participation?

We observed some geographical context. We have, for example, 2 cities that are planting courageous seeds in a ‘harder to work’ ground than others, Bistrita in Romania and Hradec Kralove in the Czech Republic: they have the least favourable context due to their communist history. Citizens themselves don’t want to have anything to do with politics, they were so much rejected they don’t see the point of involvement. We also have a third city suffering a bit, Cento in Italy, as the trust towards the stability of power structures is not high there. The average is Dinslaken in Germany and Tartu in Estonia, none of them are at the forefront, but they have a rather good context to have them emerged. And than we have Agen and Saint-Quentin in France and Santa Maria da Feira in Portugal at the forefront, already having a history of good citizen participation.

Why Portugal and France are at the forefront? I would rather think of Scandinavian countries and the e-democratic heaven Estonia.

We cannot relate the differences among the cities being one country or the other. For example, in Estonia, they are among the most advanced when it comes to participatory democracy at national government level, but not so much on local level, especially because our city partner there is a rural municipality, a group of 9 small villages. The city of Agen in France is a unique advanced case, it cannot be taken as the whole country. Its specific context is due to the mayor who decided to push the boundaries 2 mandates ago. Similarly in Portugal, it is mostly due to a political push from the mayor that makes Santa da Freira progressive. They both had already existing structures of participation; but it is the political will which put them in good use.

So we can say that the municipalities are the most suitable level of government to get people involved again in politics, because they are the closest to the people.

I would say that local is the perfect level to start citizen participation, reconnect people with decision making; but it has to go all the way to regional and national authorities as well in the process. We are trying to push a concrete change in how our democracies are working, we want involving citizens to become the new normal – whether it is to do national politics, whether it is to redesign the local square. The big danger would be to only limit it and keep it on local level.

What do you think are the ways to avoid this trap?

We need to develop experimental participatory processes on local and regional level to be future proof of concepts. Couple of years ago I worked on an EU research project CIMULACT: we created a panel of citizens (based on strict criteria) in order to give voice to citizens in the definition in the European Research Agenda in 30 EU countries. The project was a success and showed that it is possible to bring citizens’ opinion on topics as abstract as the EU research agenda, this became a proof of concept. On the longer term, if we want to protect participatory democracy, it needs to enter the regulatory framework. But you can’t make it directly enter the law without proving its efficiency and relevance. If you demand cities to do it, but they are are not convinced; they will find ways to go around it, make it useless.The most terrible would be to institutionalise participation before proving its added value to the wider audience.

Let me add that we do already have scientific proof of its added value: scientific publications argue that citizen participation does not only allow building trust, but also to come up with more relevant and efficient policies, services and urban planning.

You just referred to fake participation, please elaborate on that.

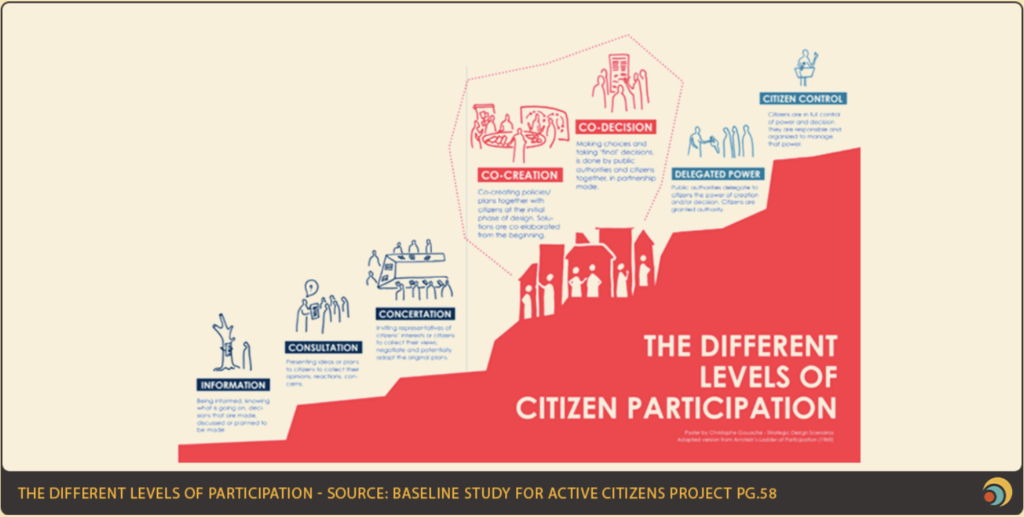

OK, let’s see Arnstein’s ladder of participation adapted to Active Citizens, where our focus is to work on the steps of co-creation and co-decision.

Let’s see level 1 consultation – experts make a 99% ready plan, and then the politicians by law or best case scenario by will, ask the citizens on their feedback. They point out some things to improve, but the plan is quite finished and couldn’t be changed much, so participation will be one paragraph saying it was discussed with citizens. It is inefficient in the context of participation, because consultation means you need to hear people out, but you don’t need to take anything they say into consideration. This is the perfect framework for fake participation.

On level 2 concertation it is slightly harder to do fake participation – you put civil society representatives, NGOs, etc. around the table to discuss your quite advanced plan which has some room for adaptation according to the interests presented. Still, the representatives of these stakeholder groups can make some noise, and if you don’t take anything they say into account, they can publish press articles and express their criticisms of the process. Here it is a bit harder to fake the participation.

If you go to co-creation and co-decision levels, it is really hard to have fake processes, because you start from scratch and you give the citizens decision power. So on these 2 levels it is extremely sensitive if you as an elected representative or civil servant don’t go all the way respecting the process. There are still some ways to fake it: in co-creation the system can be manipulated by giving unimportant things to co-create – like what should be the colour of the benches. Also, if you don’t combine co-creation with co-decision, it stays powerless. So you can have a good co-creation process, but keep the decision for yourself as an elected representative.

Which is understandable: it is a big step to arrive to co-decision.

We live in representative democracies, and the point is not to blow up the system, but to make a balance with greater participation, to find a cooperation between the 2 models. As long as the process is transparent, the co-creation process without co-decision is acceptable for the people – this is what we learnt in CIMULACT project and this is what we can see in ActiveCitizens as well. As citizen involvement is becoming a new trend and almost a must do, we will see more and more fake processes, which are more damaging than not doing participation at all. Why? Because in general the level of trust between citizens and elected officials is shrinking in Europe, so if we destroy that low level of trust by fake participation, there is a danger of pushing people even further away from getting involved in democratic processes. This would lead to even less participative processes and an even more top-down approach of governing.

Could you tell us about good examples of sharing the power in decision making, a real co-decision?

One of such successful cases happened in Agen previously to starting our URBACT project. In policy making in France there is something you call public service delegations to private companies (DSP). It can be transport, electricity, etc. sg of public interest, which service is carried out by a private company, where someone from the public sector is delegated to ensure the public interest. We have this model’s citizen version in Agen: something I would call Public Service Citizen delegation. The neighbourhood councils, built up of local inhabitants, received the official mandate from the city to make decisions on everything related to road maintenance and reconstruction – for 13 years now the neighbourhood councils decide on 100% of the road maintenance, and give the orders to the city. The technical services of the road department only act as expert consultants and support in budgeting the works needed.

It is a real risk to give 100% control of a public service to inhabitants.

Yes, it seems so, but it is working very well! There are 3 big advantages according to the mayor, and it’s been running for 13 years! 1. Before this system started to work, some neighbourhoods were flourishing, others were abandoned. Now they are all renovated at the same time, as all councils are pushing for their own territory. 2. Now they don’t have any issues related to the renovation choices and they happen quicklier. 3. They have several cases in which in some specific locations the locals found the best solution, which was not in the repertoire of the authorities.

Let me tell you a concrete story: there was a school entrance which was dangerous with cars passing. For weeks the mayor and the technical services were reflecting on possible solutions: putting bumpers in front of the entrance, introducing speed restrictions, etc. – they were not satisfied with the solutions. At the end they went to the neighbourhood council, which found the solution very quickly: let’s put the entrance to a different street! For the mayor and the technical service it was difficult to think out of the street, out of the box; while the citizens had a fresh exe on the problem and found an alternative solution, working very well!

Of course the neighbourhood councils are not perfect, there are plenty of aspects to work on, but I think it is a very interesting example of delegated power. By law the mayor has the right to veto, but in 14 years it never happened – which means that the citizens are very reasonable when given the power, extreme attitudes are eliminated, they have self-moderation. This is an important argument in favor for participatory processes.

Group dynamics work as everywhere, extremists get marginalised. That’s quite coherent.

What about the citizen control level? Do you have any good examples?

Not really, unless we regard structures between delegated power and citizen control. We have one case in the city of Amersfoort, the Elisabeth Park project.

A big park in the city needed to be rearranged, and when the city started the designing phase, the local inhabitants expressed their interest in having a say. Instead of finding ways to go around them the city decided to give the full control of the process to them: they assigned the architect to work on the plan with the citizens, who self-organised their work and prepared the plan in 4 months. By law the city authority had to hold a consultation with the citizens on the plan… there was not a single remark – obviously because it was done by the citizens themselves. In the end the mayor said very cinicly: it was faster, cheaper than if we had done it ourselves and we never had a project that accepted by so many people – so it was perfect!

Later the mayor wanted to involve the same group of citizens for the rearrangement of a square, but they said no, we have already worked 1400 hours on the park – now go and find other citizens who want to do the square!

1400 hours of work for free…

Exactly, and this is very interesting for me as it touches another question: how to avoid – what I would call – participation abuse? I am very sensitive to this question, because not only you need to care for your active citizens, but also you need to be very careful about participation fatigue. You can overwhelm your citizens with too many responsibilities – this is typically what is happening in Agen. They have the neighbourhood councils doing street management, but for the new mandate the mayor said we would like you to do a bit of cleaning, work on sustainability transition, and we also want you to animate the social and cultural life of the neighbourhood – asking from the same small number of citizens in the neighbourhood council. For me this is typically the point when they will abandon and say: I quit, you are asking too much! The city authority should not only rely on one single citizen structure, but to have multiple ones. Some of them can be long-term ones, like the neighbourhood council, but some could be temporary: could last only for the time of a weekend or for a couple of months. Cities need to play with plenty of formats, plenty of structures in order to avoid abusing citizens.

Without being too cynical, we know that public budget is restrained, shrinking a bit everywhere in Europe – citizen participation could be a very good way to have citizens working for free on things that should be supposingly done by the city. There is a difference between citizen consultation, participation and abandoning the public services.

The aspects you highlighted give quite a full picture, but there is one topic we cannot avoid: we are in the 21st century where we have the option of facilitating participation by digital techniques.

There is a separate chapter on this in the Baseline Study I prepared for ActiveCitizens network: will e-democracy save us? Clearly it will not, if it is taken as the one miracle solution. Digital tools are powerful, they increase the number and diversity of outreach, but can be used only on the condition of being properly designed and implemented into the administrative structure, funding and human resources dedicated to it.

Is there anything else you would like to highlight related to the topic of citizen involvement?

The last thing I would add is very simple: I invite cities to be brave in designing and trying out their own forms of citizen participation! It would be a pity to think that there are only a few recipes of participatory democracy. For me the greatest call for democracy would be to say: guys, let’s invent participatory democracy every day! Dare to invent ways!

An example: we are working in Agen on the challenge of building trust in elected representatives and civil servants. One of the experimentations they are doing is to develop a “coffee with an elected official”. Potentially it would be a speed date with your official: your officer would be on the street with a coffee, giving you half an hour to discuss city affairs. We don’t know if this would be feasible, time-efficient, etc. on the long-term, but it is such an interesting idea that it is worth trying out, let’s see what it gives! We are such in a turmoil that we need massive innovation, creativity, fun in exploring ways for participatory democracy.

Christophe Gouache is a project manager at Strategic Design Scenarios since 2012, Christophe studied industrial product design and responsible innovation and received his Master from The École de Design Nantes Atlantique, Nantes, France. His focus is on sustainable and social innovation, collaborative and participative scenario building, participatory foresight and service design. He is working on various projects of public policy design and public innovation with regional authorities and ministries, as well as action-research projects at EU level (#H2020). Christophe also gives courses at #INET (Strasbourg, France) and teaches “Public design and innovation” at Sciences Po (Lille).

Currently, he is the Lead Expert of the URBACT network ActiveCitizen, working on rethinking the place of the citizen in the local governance by finding a balance between representative democracy and participatory democracy