Interview with Maria Chiara Pizzorno

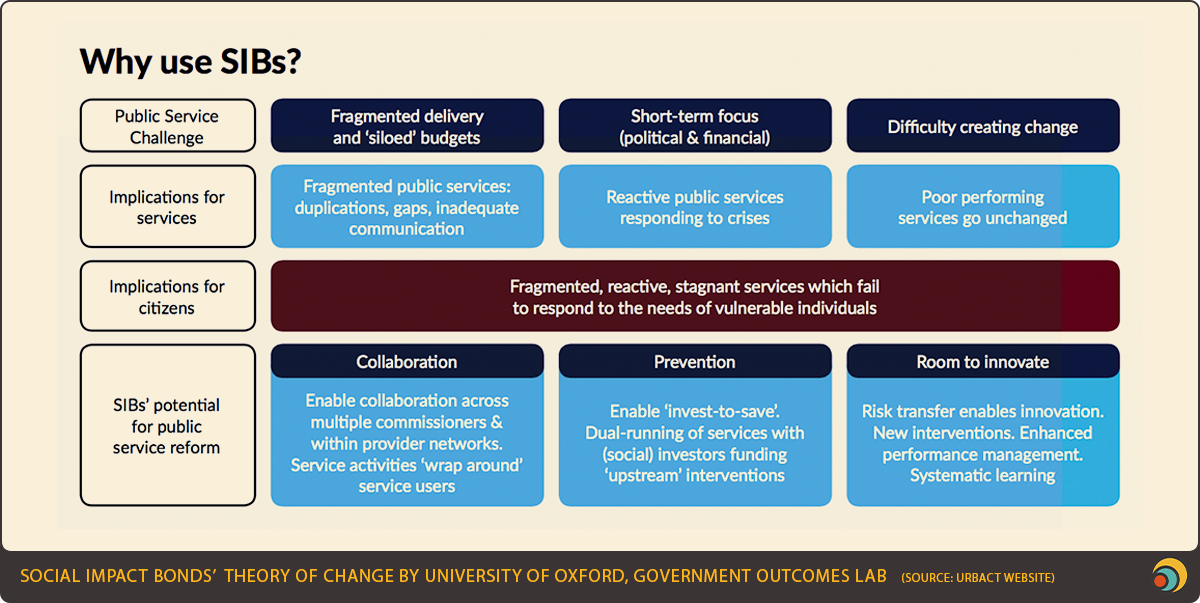

This May, we are focusing on social innovation. But for municipalities, it is a challenging topic: implementing social innovation cannot be achieved without the right financing tools. This month, we have talked to Maria Chiara Pizzorno, an ad-hoc expert in the URBACT network SIBDev. SIBDev is implementing a good practice called social impact bonds. SIBs are, on the one hand, a form of social innovation itself, but also a novel way to finance innovative social solutions. Here is our interview with Maria Chiara, slightly edited, explaining the potential of SIB schemes in financing innovative solutions to social problems.

What is SIBdev?

SIBdev is a project involving eight European cities, financed by the URBACT programme, and involving municipalities and local authorities. The focus of the project is developing social impact bonds in Europe to improve the quality, efficiency and effectiveness of social services. The eight cities involved are expected to develop a local integration action plan, which is a plan to set up their own social impact bond. They are not expected to implement a social impact bond, as that is a very challenging adventure, but they are expected to involve local stakeholders, and together with them to develop a plan towards launching a social impact bond.

Could you explain to the readers how social impact bonds work?

A social impact bond is a financial scheme to implement innovative social interventions. It starts from an outcome payer, which is a public body (such as a regional government, a national government, or a municipality). This public body then decides on a priority, a social problem. I give you an example: unemployment among young people. They want to reduce unemployment, and they set an expected social outcome, defined very precisely. In our example, we want to reduce unemployment in our municipality by five percentage points, today it is 20%, and we want to reach 15%. Then they set up an outcome-based contract, usually with investors such as bank foundations or corporate foundations, fund managers. These investors provide the upfront capital, the financial resources to finance an intervention that is capable to reach these impacts. So, they pay a service provider to implement services and actions and reach the expected goal. For example, they provide upfront capital for employment services, to offer skill development, training, or job placement to the target group. If the social provider achieves the expected outcome, they are able to reduce unemployment by five percentage points, the public commissioner will pay the investors back with interest. There is an external evaluator, usually appointed by the outcome payer (i.e., the public commissioner) to assess if the expected outcome is reached. In short, social impact bond is an outcome-based contract.

What is the advantage of a social impact bond over a traditional bank loan or bond?

Social Impact bonds are not bonds but outcome contracts. When you borrow money, through a loan, you have to return the money plus an interest, no matter what, while in the social impact bond the investor provide the upfront capital to the social provider, and if the outcomes are not achieved, they will lose all the money, on the contrary if the outcomes are achieved investors will have their capital back plus interest. So, the risk for investors is higher compared to a loan – if the investor lent the money, they would expect to get the principal amount back, whereas in a social impact bond the investor risks the capital. Similarly, bonds are debt instruments that must be repaid in full, while repayment in SIB is triggered by the achievement of the expected outcomes.

But in this case why should an investor risk their money on a social impact bond? Beyond being a good way to do CSR, is there an incentive for investors?

Social impact bonds usually involve investors sensitive to the social impact, concerned about them, such as foundations or bank foundations. In many SIB schemes (as there are many different models) the investor can select their social providers, so they want to select reliable social providers that can achieve their outcomes. Sometimes, if they see the social providers are not capable to achieve their outcomes, they have the power to say, okay, stop and we will engage someone else.

To reduce the risk taken by investors, in the last few years outcome contracts have changed. Instead of setting a binary outcome (if you reach 5%, we will return the capital with interest, but if you don’t, you lost the money), frequency outcomes are now more common. This is less risky for the investor, understanding the outcome more progressively, focusing on different levels of achievement with different amounts repaid.

How widespread are SIBs in Europe?

A couple of years ago 40 to 50 SIBs were established in Europe, the majority of them in the UK, in Continental Europe we have now around 20 or 30 SIBs. European institutions are promoting this instrument, though, so it is more and more popular, so in the future we expect to have many more SIBs in the EU.

If a city wants to start their own SIB scheme, how should they start?

You need to have a very committed and motivated team in the public administration launching the SIB, and you need political endorsement as well. This is needed as this will be a challenging, frustrating and time-consuming process. Then, you have to be very clear about your focus, the social problem you would like to address. And you need data on social issues, because you need to be very precise about the expected outcome. You need to build partnerships with social providers and investors very soon, and they must be very motivated and committed, because this is a very complex process, with organisations from various sectors, from the public sector, the third sector, and the financial sector, and there is a lot of friction. The languages and cultures of these sectors are very different, so it is frustrating and time consuming to create dialogue between the various actors in a multi-sector partnership, which is necessary for an SIB scheme.

Why is an SIB innovative?

SIB is innovative compared to traditional public procurement of services sine service providers are not paid for outputs (e.g. number of people reached by the intervention) but for the outcomes they generate, for the social change they deliver. SIB are also innovative compared to “Pay by Results” contract as in a SIB the financial risk is taken by private investors. “Pay by Results” are contract between a public commissioner and a social provider and the latter take the risk of not achieving the agreed-upon results and lose money.

What are the individual factors making an SIB successful?

SIBs rely on partnership between public, private and third sector, willingness to cooperate with a common goal – make a change for people who are suffering- is crucial. True commitment of the parties involved paves the way to success. Getting support from researchers, legal advisor, and other professionals (hopefully pro bono!) to define and measure outcomes, to achieve optimal targeting and to build a strong business case is also crucial.

Could you give an example, first, of a very successful SIB, and also perhaps of an SIB scheme that didn’t go well? What makes an SIB successful and what are the pitfalls to be avoided?

A successful SIB I’m very keen on is Energise, established in the UK to target early school leaving. They involved 3000 adolescents at risk of dropping out from school, and the scheme was successful, the investors were paid back. But what was really interesting is the intervention model, as SIBs aim to finance innovative interventions. This was very innovative, supporting adolescents in school and outside school, giving them tutors, a multi-action intervention with a very risky target.

One unsuccessful SIB was, I think, in the United States, giving cognitive therapy to ex-prisoners to reduce incarceration. But it seems it has failed, but I’m not very familiar with this case.

Is it normal for a SIB to be paid back? If I’m an investor, there’s an SIB in my city, I do background checks on the social providers, can I expect the target will be met and I will be paid back?

Yes, the majority of SIBs implemented so far were successful and it is clear why: it is a win-win. Everyone is interested in its success, the outcome payer (the public commissioner) wants the SIB to be successful, the social provider wants to succeed, and the investor wants that too. Everybody at the table wants to succeed, even if for different reasons, and that is why so many SIBs have been successful. And the public commissioner and the investor negotiate the outcomes, so there is room for negotiation as well to set feasible, viable, achievable outcomes.

Are there areas of social interventions where SIBs are more successful? Is it true that, for example, unemployment is a suitable issue for a SIB scheme, whereas, say, healthcare is less suitable?

Many SIBs are in employment and education, and it is easy to see why. It is easy to measure the outcomes. The crucial point for an SIB is outcome measurability. You must be able to define and measure the outcomes. When you have very complex social issues, it might be difficult to set the measurements of success. The health sector is another sector where SIBs are increasing, because health outcomes, too, are relatively easily measurable and definable, even mental health and wellbeing is measurable. There are plenty of ways to measure health outcomes.

But, for example, drug addiction is an area in which it is difficult to define what is success and set a time frame to measure this. With some topics, the definition and measurement of success is very problematic.

And in some sectors, like education, employment, or health, you can rely on a strong background of social providers. You can involve social providers with a strong track record. In other sectors, where an effective intervention model is not in place, so it is going to be riskier.

If you are interested in learning more about SIBdev, you can find more info here. If you want to find out more about how to develop a SIB, the UK Government has a step-by-step guide that is largely applicable outside the UK, available here.

Maria Chiara Pizzorno is an expert in education, social innovation and social impact investing. She has a PhD in Psychology of Health and Quality of Life from the University of Turin and the University of British Columbia. Maria Chiara has been involved in several European projects related to social impact bonds. These included ALPSIB, funded by the Interreg Alpine Space programme, SIB FOR GROWTH: Education & Integration through Social Finance, funded by the EU Programme for Employment and Social Innovation, as well as the URBACT network SIBdev.

Additionally, as an education expert, Maria Chiara has focused on preventing early school leaving, and promoting career development and mobility among disadvantaged students.