According to the International Union for Nature Conservation itself, which launched the very concept of nature-based solutions, agriculture is the most important issue and the biggest opportunity for nature-based solutions in our days. By now we know that with the methods of regenerative agriculture it is possible to multiply the amount of soil organic matter in a few years on a large-scale farm while reducing the use of chemicals and machines, but not necessarily reducing yields. Yet, new – regenerative – ways of farming proportionally lag behind intensive agriculture – why is the transition taking so long?

In the ominous shadow of certain phenomena of the ecological crisis, particularly global climate change, there is a lack of discussion of soil life and soil degradation on the global scale. The grave results show that the paradigm shift in agriculture is inevitable and speeding up the transition is of utmost importance.

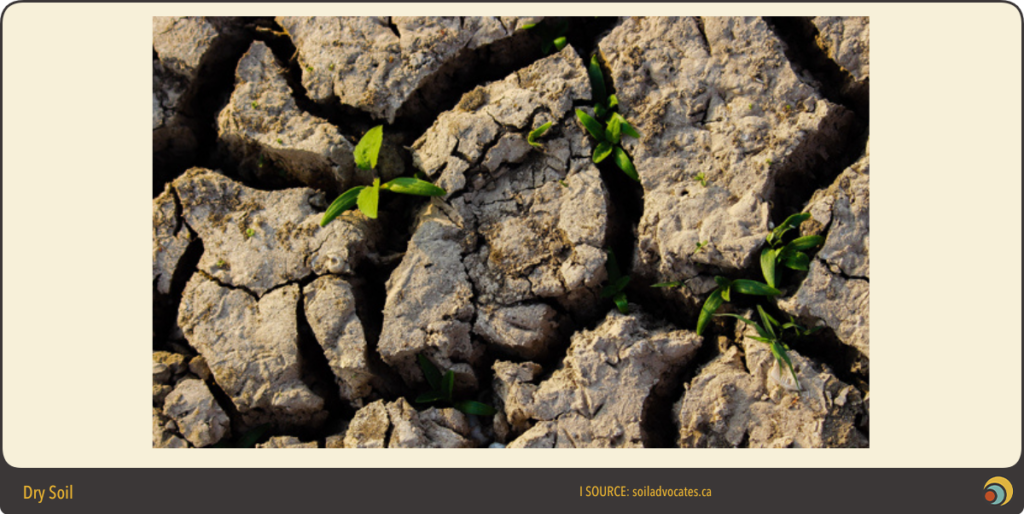

Let me quote the excellent documentary Poisoned Soil – “By 1950, half of the world’s land supply had been rendered unfit for cultivation by increasingly intensive agricultural technology. Around half of Hungary’s land is under cultivation, but 2/3 of the cropland is threatened by some form of soil degradation that reduces fertility.” According to the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), droughts, heat and water scarcity will make production impossible on a third of the world’s cropland by the end of the century. Soil moisture in nearly half of Europe’s agricultural areas has declined substantially in recent decades (while agriculture in general uses and consumes 70% of freshwater resources). It is therefore clear from the data that there is also a dramatic erosion and deterioration of soil quality, which intensive technology users believe can be offset – for a time – by increasing fertilisation. In the meantime, more and more people need to be fed, the historic drought with its heat waves has caused hundreds of billions of dollars in (agricultural) damage and serious health risks, and now the supply chains are being disrupted. Many of us ask the same question: if we are currently in the last moment to save the soil, isn’t it a now and here moment for change, to finally produce healthier food while improving the environment and sequestering a lot of carbon dioxide?

Unveiling the great myth of agriculture

Any agricultural system, even a very biologically degraded cropland, is inevitably a complex ecological system where everything is interconnected and its functioning is fundamentally determined by laws of nature.

One of the main causes of these highly negative trends is the environmental destruction caused by large-scale farming technology. In addition to the intensive use of chemicals and the radical degradation of biodiversity, this includes that deep tilling disrupts the biology that creates healthy soil and the impact that would have on the environment in terms of water retention, irrigation, since as a result of deep tilling, a dense, impermeable layer ca. 20-30 cm below the surface significantly prevents water from seeping down to the depths and contributes to the formation of inland water. In addition, deep tilling destroys soil microorganisms and reduces soil life by a tenth. Deep tilling not only destroys the incredible biodiversity and water-retention capacity of the soil: it also radically reduces the humus content of the soil, while ploughing releases large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The nutrients needed for growth must therefore be artificially replenished – says the system of intensive agriculture.

According to regenerative agriculture, there are other, more sustainable ways to cultivate our lands. The nutrient content of the soil depends to a large extent on the amount of soil organic matter. Just think what happens to the straw in the forest and what happens to the stalk-less field. The humus content of soil depends on the amount of life (worms, fungi, insects, micro-organisms) in the soil, and on the extent to which it can break down organic matter and mix it with soil particles. The problem with deep tilling is that micro-organisms that live closer to the surface and use more oxygen die off as they go deeper, while their counterparts in the deeper layers of the soil, adapted to the oxygen-poor environment, multiply as they get closer to the surface and use up the humus. The result of deep tilling is a significant loss of nutrients in the topsoil, but it also reduces the soil volume permanently, as the soil loses its crumbly structure and turns to dust, which is washed away by water and blown away by the wind.

The solution is nature-based

The radical transformation of farming techniques, the rise of so-called ‘’regenerative agriculture’, is both a solution to the major problems the current agriculture system is facing (drought, inland water, erosion, loss of nutrient values) and a major climate change mitigation measure. “Regenerative agriculture” is defined by Terra Genesis International (2020) as “a system of farming principles and practices that enhances biodiversity, enriches soils, improves water conservation and supports ecosystem services. At the same time, it helps to stabilise yields and enables the development of agricultural systems that are resilient to climate change”.

Regenerative agriculture involves little or no soil disturbance and prioritises continuous soil cover (with cover crops or mulching) to reduce evaporation losses. The latter is important because soil is the best water retainer: the soil organic matter can absorb ten times its own weight in water, as the public could witness in the drought that peaked in the summer of 2022.

Restoring soil health is therefore one of the foundations of restoring soil biodiversity, which by definition is a nature-based solution. In other words, it is an action to protect, manage and restore natural, or in this case human-modified, ecosystems in order to address pressing socio-economic challenges, to increase human resilience to the adverse effects of climate change and to enhance biodiversity.

However, this is not a matter of the moment: soil restoration requires a process of around 10-12 years. The degradation and erosion of soil is such that the ecological conversion of agriculture can wait no longer. And this is why, as with so much of the ecological crisis, the cultural-economic question of paradigm shifts arises: on the one hand, a set of useful ecosystem services that can be monetised, and on the other hand: profit, habits and beliefs. At the same time, the damage of the drought of 2022 has led to more and more people talking about the need for regenerative agriculture, which yields and profit, taking into account the low input demand, can measure up to the same level as in large-scale intensive farming.

Agroecology

It is worth clarifying agroecology, as it is both a scientific discipline, a set of practices and a social movement. “The rise of agroecology has been a response to the problems caused by industrialised agriculture; its scientific foundations are rooted in agronomy, ecology, social sciences and economics,” says the website of one of the movement’s Hungarian representatives. It also follows that no-till farming is only one element of agroecology, albeit an important one. Restoring soil life is undoubtedly key, but increasing and enhancing biodiversity and ecosystem services is a more complex issue. Agroforestry – which is a nature-based solution -, livestock farming and the transformation of the whole food system all play an important role in it.

Regenerative agriculture is an effective response to the global phenomenon of soil degradation, but it does not mean avoiding herbicides by all means. However, its organic approach seeks to apply as few inputs as possible to the land and to keep weeds at bay with animals or special mechanical solutions.

Also of paramount importance for the ecological crisis is the fact that without deep tilling, the soil has the potential to remove very large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A system similar to the industry’s carbon quota system is in operation, helping farmers to sell credits on the quota market for the proportion of carbon removed from the soil.

Everything seems to be in place for a paradigm shift. So why are the environmentally friendly farming practices described above not spreading more widely? Maybe we need more “motivation”, like more drought years, similar to the one we had in 2022…